In March 2019, Mario Ochoa held his 4-year-old son and prayed that his cough would go away so they could sleep. Castiel’s “terrifying” snoring kept Ochoa awake. Ochoa described it as watching his son drown. “He gasped in his sleep.”

At Intercontinental Terminals Company, a Texas-based company owned by Japanese giant Mitsui series, a series of large tanks storing millions of gallons of extremely volatile chemicals used to create plastic and gasoline caught fire. After a tank pump failed, naphtha leaked and started the fire.

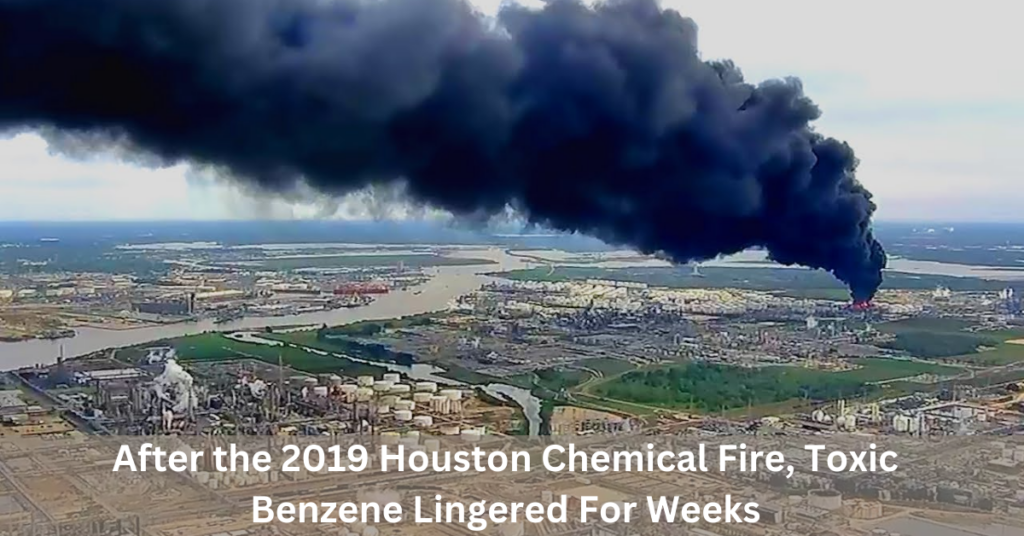

An eerie black smoke plume rose above Houston as the ITC fire expanded from tank to tank. Ten tanks, each holding over 3 million gallons of chemicals, collapsed, spilling toxins into the ship channel and k!lling birds and fish. Neighborhoods received ash.

Toxic Benzene Lingered For Weeks

Deer Park, the city closest to the fire, instructed residents to stay indoors twice. After the fire, air monitoring discovered abnormally high amounts of benzene, an invisible, sweet-smelling chemical prevalent in crude oil and cigarettes. Repeated exposure can cause cancer and throat and eye irritation. Benzene can produce dizziness, fast heart rate, and headaches when inhaled in excessive amounts.

Federal, state, and municipal officials failed to inform Ochoa and other residents that an invisible threat remained after the fire was extinguished. According to a Texas Tribune examination of U.S. Environmental Protection Agency air-monitoring data, benzene emissions soared to unsafe levels for more than two weeks after neighboring residents were advised it was safe to return to school and work. After the fire, a mobile laboratory collected data for two months.

Texas Poison Center Network records reveal its hotline got roughly 200 complaints alleging chemical exposure from the ITC fire over a two-week period. Nearly 1,000 individuals visited temporary mobile health clinics in Deer Park for three days after the fire erupted. Headache, throat discomfort, nausea, coughing, dizziness, and vomiting were common.

After the fire had been out for days, Ochoa, a 39-year-old pipe worker at an industrial construction company, stayed up worrying about his son, who complained of a headache. Ochoa hugged his son and hid under some pillows. He felt helpless. “He doesn’t even realize he’s suffocating,” he claimed. Next morning he took his son to the hospital.

VIDEO: On March 17, 2019, a set of giant chemical tanks at Intercontinental Terminals Company in Harris County caught fire, spewing large amounts of benzene, a human carcinogen. The Texas Tribune found benzene levels remained unsafe for weeks after the fire. The Texas Tribune/Anita Shiva and Todd Wiseman. You can see the youtube video below:

The EPA, Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, and Deer Park had to decide how much benzene was safe to breathe a few days into the crisis. They opted to provide public warnings only when benzene levels hit 1,000 parts per billion in the air over one minute, which scientists now consider excessively high. After the fire, federal, state, and local agencies formed a “Unified Command” near the ITC site to set a benzene threshold. The federal workplace norm allows 1,000 parts per billion over an 8-hour work day.

The action level used during the ITC fire was “out of line with basically every other measure I’ve seen [for] benzene,” according to senior analyst Anita Desikan, one of the authors of a December 2022 study of the fire. She added, “You will see people hurt and harmed if it’s your only number for taking action.”

An EPA official claimed the agency would “get it out to the community to take action” if benzene levels exceeded that level at a March 26 press conference, nine days after the fire erupted. “If it’s 1,000 parts per billion, we’ll let you know.” But not usually. They arrived late for residents to act.

The Tribune’s analysis of EPA data obtained by the nonprofit Environmental Defense Fund shows that benzene spiked above 1,000 parts per billion on at least seven days after the second and last shelter-in-place advisory expired, but it’s unclear if those spikes lasted for 1 minute.

On March 31, two weeks after the fire started, benzene spikes above 1,000 parts per billion were found in a Deer Park residential area. TCEQ’s stationary and portable monitors showed increased benzene concentrations at the same periods and places as the EPA’s mobile lab.

“Benzene drifting through Deer Park was a health threat to the community that went basically unshared,” said Elena Craft, a senior scientist at the Environmental Defense Fund. Craft said no one grasped the magnitude. “Or still don’t.”

Deer Park Mayor Jerry Mouton told a reporter that the strong smells that persisted for a week after the fire were “normal.”

“There are random times when we have smells,” said Mouton, who denied multiple interview requests. “We are monitoring the air continuously, and there’s nothing even close to registering any kind of action item.”

According to the Texas Department of State Health Services, the incident had “no longer-term public health impacts to the community,” ITC told the Tribune. The research determined that benzene health impacts “were not expected to have occurred” because to the “short” time high levels were identified.

Mario Ochoa and his son Castiel Winchester sit on a rock in Hermann Park on Feb. 25. Ochoa took his son to a park near his southeast Houston house days after the 2019 ITC fire. “I didn’t even think about the contamination if he was rolling around playing in the grass,” Ochoa said.

Mario Ochoa and his son Castiel Winchester sit on a rock in Hermann Park on Feb. 25. Ochoa took his son to a park near his southeast Houston house days after the 2019 ITC fire. “I didn’t even think about the contamination if he was rolling around playing in the grass,” Ochoa said. The analysis ignored the reality that hundreds sought medical attention during the incident.

According to EPA spokesman Jennah Durant, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, a Department of Health and Human Services branch, examined the action level “and had no objections.”

CTEH did hand-held air monitoring for Deer Park and ITC. Pablo Sanchez-Soria, a senior toxicologist at CTEH, wrote that measuring benzene levels for one minute in the community helps regulators “take early action” to decrease human exposure. Sanchez-Soria said the 1,000 parts per billion action level for benzene across community areas was cautious. “Sufficiently protective values must be balanced against the inherent risk of evacuation.”

Seth Shonkoff, an environmental health sciences associate researcher at the University of California-Berkeley, said it’s “inappropriate to use occupational standards in a community setting” because they’re designed for healthy adults trained to prevent chemical exposure with respirators. He said that workplace guidelines balanced outmoded benzene science and commercial economics. You can check out the recent news about TurboTax Will Pay Over 465K Texans

Texas sets benzene’s health risk at 180 parts per billion per hour. The state health department used that number to assess health risks from the ITC fire, but TCEQ spokesperson Victoria Cann said it “does not constitute a bright line” and is “precautionary in nature.” The agency doesn’t regulate emissions over that level.

A group of mostly Houston-area scientists using the latest science on benzene exposure said that officials should have used a much more conservative threshold—27 parts per billion in two consecutive hourly readings—and issued seven more shelter-in-place orders and 17 air quality alerts after the fire. Houston Health Department-commissioned study pending peer review.

Harris County commissioner Adrian Garcia, who represents Deer Park, said the county was “scrambling” to receive air quality data from the corporation or federal and state agencies to make their judgments. Garcia said the government strives to be fair without overreacting. We wanted to be fair to the sector and truthful to the public about whether there was still harm.

“I’m not sure we got there,” he remarked. Four years later, Deer Park residents who fell ill—some youngsters, elderly, or at higher risk—said they felt exposed to more pollutants than warned. Like Ochoa, many are still traumatized. Ochoa, 43, called that turmoil unsettling. Soul remembers.

Four Years Later

Federal inspectors are still investigating four years after the ITC fire sickened Ochoa, his 62-year-old mother, his son, and many others. Expect a final report this year. Ochoa and Contreras are two of more than 300 Houston-area residents suing ITC for health issues like headaches, coughing up blood, respiratory infections, and mental stress from the 2019 fire, which Ochoa is trying to forget.

“I try not to think about it because my heart feels it,” Ochoa added. He still has panic attacks late at night when he thinks about that week of the fire. “I feel that sorrow,” he remarked.

The complaint also demands that the business cover residents’ cancer screenings and doctor visits. Some municipal officials now concede they should have communicated with the public more as air quality worsened and are revising their processes.

“It’s all fine, up until all of a sudden it’s terrible,” said Loren Hopkins, Houston’s Chief Environmental Science Officer.

Hopkins said people need to make their own decisions. “Public data needs interpretation.” In an interview, Harris County Pollution Control Executive Director Latrice Babin said that telling citizens to shelter in place is “a really hard call to make” because air quality testing depends on weather and location, even when high chemical levels are recorded. Sunlight can turn pollution into smog, strong winds can swiftly disperse it, and tests taken near highways can detect car pollution.

The city’s 2020 benzene guidelines, far lower than those used during the ITC incident, recommend a shelter-in-place advisory if benzene levels exceed 72 parts per billion for an hour and evacuations if they exceed 200 parts per billion. Harris County analyzed response failures. During the 2019 fire, Harris County Pollution Control, which has a dedicated squad to respond to hazardous material and chemical fires, had low staffing and “antiquated” or out-of-service equipment. Harris County commissioners spent over $11 million on report implementation. Harris Agency Pollution Control spokesperson Dimetra Hamilton said the agency had doubled staffing, launched a community air response monitoring program, and bought more emergency response equipment.

Harris County is spending $1 million in American Chemistry Council funding to establish a chemical catastrophe response plan. The Tribune obtained a draft that lists 22 chemicals, including benzene, potentially harming inhabitants but does not specify a shelter-in-place level. Deer Park did not respond to concerns regarding whether its community benzene exposure policies have altered. The chemical leak caused disagreement over who should warn residents to shelter in place.

Mario Ochoa and his son Castiel Winchester sit in the van after walking through Hermann Park in Houston on Feb. 25. Four years after the 2019 chemical fire, Ochoa’s 8-year-old kid has sinus infections and avoids playing outside. Mario Ochoa and his son Castiel Winchester sit in the van after walking through Hermann Park in Houston on Feb. 25. Four years after the 2019 chemical fire, Ochoa’s 8-year-old kid has sinus infections and avoids playing outside.

Harris County Fire Marshal’s Office assistant chief Rodney Reed said cities and county agencies can issue shelter-in-place advisories. However, determining jurisdiction at an unincorporated county institution like ITC might be difficult. Officials chose Deer Park and ITC to lead the reaction.

Since 2019, the TCEQ has added new air monitors in the ship channel area and bought three new air monitoring trucks. The state renewed ITC’s Deer Park chemical permit less than a year after the fire. A public hearing will address safety concerns over ITC’s operations permit renewal in May. We have the latest Texas news about League City Infrastructure Maintenance For Safety

Due to the ITC fire, TCEQ staff lobbied for a rule change in 2021 that allows the agency to consider catastrophic explosions or fires when issuing licenses to companies. Attorney General Ken Paxton, who handles significant industrial accidents, received the ITC case from the TCEQ. Paxton’s office sued the corporation in 2019, but Travis County District Court records show little progress since 2021. The attorney general declined interview requests.

In a written statement, ITC said it continues to install “enhancements to safety, environmental integrity and emergency response capabilities” at Deer Park. The corporation added gas detectors and emergency shutdown valves to numerous parts of its facilities. Residents still blame the tragedy for health issues. Ochoa’s 8-year-old son Castiel has sinus infections. The chatty kid, who told a doctor that his breathing troubles felt like “bugs getting in my nose, like little tiny worms” clogging his nostrils and lungs, is now afraid of playgrounds, his father claims. They prefer video games indoors.

Ochoa left pipe-fitting for a non-chemical career. Ochoa said he heard horror stories from other refineries about people becoming sick. “It’s terrifying. As a single dad with a child, I must find an alternative way.” Contreras now looks for unexpected aromas and smoke at adjacent chemical companies. She feels obligated because her grandchild has breathing troubles. “Do you have anything to cover up?” she asks relatives and coworkers when she sees anything dangerous. “For self-defense?”

Contents